Boeing 777X: The New Competitor in Air

This year’s Farnborough Airshow was a little bit different. There was anticipation amongst the unusually dry and hot weather; the sun shone…

This year’s Farnborough Airshow was a little bit different. There was anticipation amongst the unusually dry and hot weather; the sun shone fiercely on the tarmac as what sat on it had all eyes at the airshow glued on— the 777X.

Designed and produced by Boeing, the 777X is Boeing’s answer to modern multi-haul jet airliners. Its predecessor, the 777–300ER (extended range), was a major success. First flown on February 24th 2003, it was at that time one of the most practical jet planes due to its size, the ability to fly long distances and its ETOPS 330 rating. At present, the 777–300ER is still a common sight, with up to 799 units delivered, 844 orders received and 68 airlines as its customers. It is no doubt the 777–300ER was highly profitable, so Boeing wants to bring the glory back.

Design

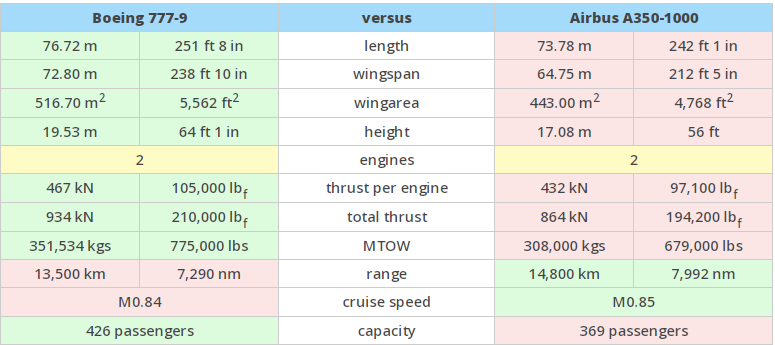

The 777X is massive. Its length is close to 76 meters, and is currently the longest commercial jet ever built. With a wingspan of 72 meters, it is so long that its wingtips fold when on ground to prevent the wings striking other planes. It comes in two variants, the 777–8 and the 777–9. The 777–9 is slightly longer and can travel further than the 777–8.

Its fuselage (main body) is made of classic aluminum alloy, a material known to be lightweight and strong, with a small percentage of carbon fiber. Although Boeing’s new planes like the 787 are made mostly of carbon fiber composites, which are lighter, stronger and resistant to corrosion, Boeing defended its choice by stating the 777X is a derivative of the older 777 variants (eg. 777–300ER), not a whole new aircraft. The 777X’s wings however, are fully made with carbon fiber composites.

The 777X is powered by a pair of General Electric’s GE9X engines, tailored specifically for this aircraft. Its maximum thrust is a whopping 490 kilonewtons, recognised as the most powerful jet engine by the Guinness World Records. It is also the largest commercial jet engine, measuring at 4.1 meters wide and 5.69 meters long. It has a bypass ratio of 10:1, the higher the ratio is, the more efficient the engine is. Why is that so?

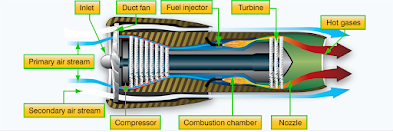

First, we need to know how a jet engine works. Incoming air is captured by the inlet and some of the air passes through the fan, then through the core compressor and burner (combustion chamber), where it is mixed with fuel and combustion occurs. The hot exhaust then passes through the core, turbines and exits the engine through the nozzle. The rest (most) of the incoming air only passes through the fan and bypasses, and goes around the engine. The bypassing air has its velocity increased, without involving combustion. The hot exhaust, together with the bypassing air, produces thrust. So it can be concluded that a jet engine has two sources of thrust.

Bypass ratio is essentially, the ratio of air that only passes through the fan to the air that passes through the engine’s core (also known as the shafts, compressors and turbines) for combustion. If there is more air that only passes through the fan, more thrust per unit fuel is produced, which is why a higher bypass ratio is more efficient.

Airbus’s A350–1000, its Main Rival

The A350–1000 is slightly older. Designed and built by a French commercial jet company, Airbus, which is Boeing’s main competitor; it commenced its first flight on November 24 2016. People always compare planes made by Airbus and Boeing due to serving the same purpose-commercial use. The A350–1000 is sort of a benchmark for Boeing to design something better, so the 777X was Boeing’s answer. Let’s compare them with the -9 variant.

Judging by the numbers, both planes have their pros and cons. The 777–9 is bigger, more powerful and can fit more passengers. Meanwhile, the A350 has a lower Maximum Take-off Weight (MTOW), a longer range and a higher cruise speed (this is without considering factors such as payload, air temperature and humidity). The A350’s lower mass is due to the fact that its whole body (both the fuselage and wings) is made of carbon fibre composites, which are less dense than aluminium alloy in the 777X. Both the A350 and 777X have received the ETOPS rating of 180.

In the commercial aviation industry nowadays, size does not matter as much as it used to be. Cost-efficiency is, for most airlines, the number 1 priority. The glorious days of massive, double-deck commercial jets such as the Airbus A380 did not last long. Due to its large capacity catering for more than 500 passengers with four engines, it consumes a lot of fuel and is rarely filled up. This deters airlines from using them as it is simply not cost efficient.

Using twin-engine jets is a good step towards sustainability, economically and environmentally, which is why planes like the 777x and the A350 are getting a lot of recognition. Malaysia Airlines is selling its Airbus A380’s, which were famous for the Kuala Lumpur-London route. The airline replaced them with A350’s instead.

The Airbus A380–800 variant (left) and the Airbus A350–900 variant (right) in Malaysia Airlines’s Livery

In my opinion, aircraft manufacturers are headed towards the right path. Of course this does not take the factor of improper quality inspection into consideration, like what happened to Boeing a few years ago with the MCAS system in the Boeing 737 MAX, but that is a whole other story you can check out. “Bigger is better” is slowly getting less relevant. We have limited natural resources, so we must use them wisely. Even ethically speaking, the role of engineers is to not just create something revolutionary, but also make it eco-friendly and sustainable.

[Written by: Amirul Haziq bin Amri Edited by: Teoh Jin]