Could the People Against Undi 18 Have a Point?

As a super curious soul who enjoys exposing themselves to a variety of opinions and learning about other people’s perspectives, I one day…

As a super curious soul who enjoys exposing themselves to a variety of opinions and learning about other people’s perspectives, I one day randomly asked an adult in my life whether they supported Undi 18. To my surprise, they replied that they didn’t. The reasons behind their opinion sparked my curiosity and inspired the creation of this article — the debate of Undi 18 and how the concerns regarding the bill could actually be valid. Ready? Let’s begin.

What is Undi 18?

Undi 18, a bill that proposed the amendment of the Malaysian Federal Constitution to lower the voting age from 21 to 18, has passed and will be implemented by the end of 2021. This means that in the next election, many young adults aged 18 and above will be able to vote. Many of us will finally have the power to turn our thoughts into action and our hopes for Malaysia into a reality.

The many arguments supporting Undi 18 have already been widely covered in various news articles and social media posts. Thus, I shall simply summarise some of the arguments as efficiently as possible so we can explore the validity and legitimacy of the arguments not spoken about as often, the concerns that hold back some from supporting Undi 18.

Arguments supporting Undi 18

First, let’s address the topic of maturity. 18 year olds are already adults according to Malaysian law. They can drive, work, pay taxes — contributing to the economy, and even get married. This is probably why the legal voting age in most countries, over a hundred nations worldwide in fact, is 18. Some even argue that the issue of maturity is impertinent as the age gap between 18 and 21 year olds is simply that of 3 years, and that young adults aged 18 to 20 carry the same weight of responsibilities as their 21 year old counterparts who are also likely working or studying.

The youth could be the fresh change that revamps our politics and propels our country forward. In light of Malaysia’s recent political instability, multiple changes in government, and backdoor government incident amongst other political incidents that have let down the Malaysian people, many older Malaysians have lost faith in our democracy because of how different the reality of our country looks compared to the hopes of the people back when we voted in the last election. Having the voting age lowered could inject millions of new, young voters into our system and bring about the necessary change that our politics, our country, and our people need. It gives us hope that things can change now, and not in 100 years when some of us are no longer here to witness it.

Some older people claim that the younger generation is not interested in politics but that’s not true. We want our country to be better. We would love to be able to vote for representatives that represent our values and have our ideas be heard. There are numerous teenagers and young adults who use the internet and social media as tools to keep themselves updated and share information on domestic and global issues like human rights, education, climate change, economics and more. Perhaps not every young adult is interested in politics but not every older adult is either. For those of us who do care, who do want to make a difference, we’re here and we’re excited for the opportunity to make an impact.

“Everyone claims that young people are the future so shouldn’t we be able to choose what our future will look like? What our fates will be?”

In the end, don’t our voices and our wishes deserve to be heard and accounted for?

Arguments against Undi 18

Now, this is where things get interesting.

Argument number one: teenagers and young adults are naive as they lack exposure and experience in the working world. What if they make terrible choices due to negative political influences and peer pressure, jeopardizing our country’s future?

It’s easy for us to pass off any arguments against Undi 18, our right to vote, as ageism, as older Malaysians looking down on the young, treating us like clueless newborns and depriving us of our rights. However, perhaps listening to the concerns of the other side could help us prevent their worries from manifesting and coming to life, or at least reduce the magnitude of any possible negative impacts.

Some older Malaysians are concerned that at 18, 19 years old, younger Malaysians who are not very exposed to the world of Malaysian politics and who do not have access to relatively unbiased information, might just listen to what their parents say and vote accordingly.

As a student in a private college like Taylor’s, who has had access to technology, social media and the internet since I was ten, I acknowledge that I have a certain amount of privilege that not every Malaysian teenager has. Some younger Malaysians are too busy juggling working to support their family, helping to take care of their siblings, house chores and studying to have the time or the energy to read about the ever changing climate of Malaysian politics, if they even have access to such information at all.

According to our education ministry, research shows that 36.9% of Malaysian students nationwide don’t possess any electronic devices. They don’t have the means to attend online classes during this coronavirus pandemic, much less read about Malaysian politics and educate themselves on the past histories and actions of the political parties in their free time.

Students are not taught politics in most schools, perhaps due to the concern that the political beliefs of the teachers might seep into the education provided to the youth. Some teenagers are even told when they inquire about politics, to “not worry about it as it is for adults” and that they will “know when they get older”. So maybe that plays a part in why, to quote a source from MalaysiaNow, political literacy is not an accessible topic for young teenagers.

“I think my generation isn’t ready because we don’t have the freedom to talk about it. We can’t even name politicians in our examinations because they portray politics as something that we should avoid.”

- Nurul Rifayah Muhammad Iqbal, 18, from MalaysiaNow

Many students would likely have to rely on hearsay from their families, teachers and friends when making their decision on who and which party to vote for, a decision which is affected by alarming but powerful elements known as bias and propaganda.

Exhibit A: In 2013, a video called “Listen! Listen! Listen!” went viral on social media, and no, it was unfortunately not about Beyonce’s iconic song, Listen. At the start of the video, students at a student forum event hosted in UUM, Universiti Utara Malaysia, were asked to recite a pledge opposing street demonstrations, referring to the BERSIH civil society movement that sought to reform the Malaysian electoral process for clean and fair elections. Some critics say that this pledge was an attempt to brainwash the students.

A guest speaker named Shafirah Zohra Jabeen then gave a speech, criticized by some for trying to ignite hatred towards Barisan Nasional’s opposition party and the BERSIH rally organizers and as an attempt to politicize the event, and which led to a viral, heated confrontation between her and a Malaysian law student named K.S. Bawani. Bawani bravely confronted Shafirah about her pro-government stance on a number of controversial public policies, highlighting points on BERSIH and free education in Malaysia, when she was abruptly and rudely interrupted by Sharifah who snatched the microphone and cut her off by repeating “listen, listen, listen”. Shafirah did not just shut Bawani down in the middle of her valid argument but also berated her in front of an entire hall of students.

Shafirah dismissed Bawani with statements such as, “when this is our programme, we allow you to speak”, “when I speak, you listen”, told Bawani to leave the country if she was not happy here and finished with the fantastic, totally valid argument of “even animals have problems.” Note the sarcasm.

This is proof that age does not equal maturity and that there are some young Malaysians who are more mature and capable of formulating rational arguments compared to some older adults.

However, the reason why I brought up this incident was because of the disturbing and glaringly obvious difference between how loud the claps and cheers were for each side. There were still a lot more students rooting for Shafirah than there were for Bawani, loud cheers and claps for the woman who had rudely berated a student with dismissive, weak retorts in front of a crowd of more than 2000 university students, some of which were aged 18 to 20 years old.

In the spirit of critically analyzing the validity of all our evidence, that video was released more than 9 years ago. Things have changed a lot since then, thanks to advancements in technology, social media and an increase in digestible political content, just to name a few factors. Things are much more different now than they were back then. If a similar event occurred, perhaps more students would cheer for Bawani, tell Shafirah off, or even get up and force their way out of the hall. Teenagers in today’s day and age are more willing to speak up against members of “authority” if it means standing up against injustice, so who knows? Maybe such an incident would never occur now. I certainly hope so.

So, do I think all young adults are easily swayed by propaganda and do not have a mind of their own? Of course not. But, are the minds of young adults, at the age of 18 to 20 years old, impressionable? Some Malaysians think that the young adults in that age group are still not ready yet because many of them are still studying in university or have just started working, and have yet to meet different people of all walks of life that might expose them to different opinions compared to the ones they might have heard growing up their entire life.

Exhibit B: Utusan Malaysia. What if they, their families and their friends are continuously fed propaganda infused with hatred, prejudice and misinformation for years?

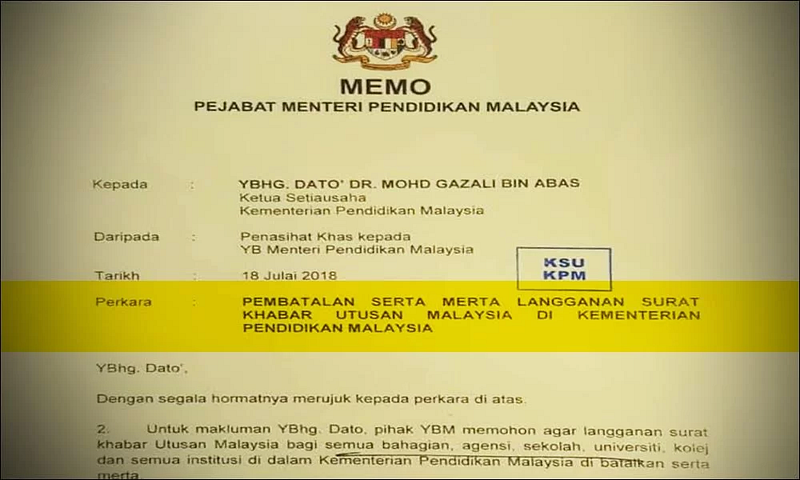

Before Pakatan Harapan won in 2018 and issued a directive to the education institutions to cease all subscriptions, Malaysian schools, colleges, universities and other institutions under the Education Ministry were obligated to subscribe to Utusan Malaysia, an UMNO-owned newspaper considered to be a mouthpiece for the previous ruling party. Utusan Malaysia has been accused of religious bigotry, unfair reporting and stirring racial discord with lies and misinformation. They have also had many defamation suits.

One of the main reasons why Barisan Nasional (BN) was able to stay in power for so long is, to quote a journal published by the Cambridge University Press, “the extensive influence they exercised over Malaysian media, which has led of a strong media bias in favour of BN and against opposition parties.” Utusan Malaysia was believed to have been widely circulated in rural areas, which helped parties like UMNO win rural votes, enabling them to win and stay in power. Having witnessed the impact of such propaganda and experienced that historical baggage, some older Malaysians are worried that 18 to 20 year olds who live in rural parts of Malaysia, who don’t have access to social media or the internet and or have only been exposed to information deriving from biased newspapers, might lead to an abundant of votes for UMNO and cause them to win again, a method that had worked for BN for a long while. Now that UMNO is back in power…

However, perhaps Malaysians with those worries might be able to relax more when they remember that despite the gerrymandering and malapportionment by the Election Commission related to the 2018 election, and the efforts to cause voter suppression by the BN government, Pakatan Harapan still won according to the wishes of the majority of citizens. Remember that in the age of verified infographics on the internet and social media, more young people have access to digestible information not propagating hatred. So perhaps things are actually different now, and as long as all of us, regardless of our age, take the steps to educate ourselves with verified information and become better-informed voters, our democracy won’t be in as much of a crisis after all.

How to become a better-informed voter

Educate ourselves — Learn more about your country’s politics. For example, you could read reliable news sources about who the major political players are, what the parties stand for, their accomplishments and failures, and some of the major political incidents that took place in the past.

There’s this fun website called MyMP that tracks all 222 Malaysian politicians to see what they’re really doing for their constituents! The MPs have cute little avatars and are scored based on five categories: availability, loyalty, work ethic, transparency and win rate. Find out who your representatives are, and check them out here!

3. Share verified information with friends and family — make sure the information comes from a trustworthy news source. It’s better if they have sources, statistics and research to back up their statements.

4. Chat about politics in everyday conversations — Remember to keep an open mind and remain respectful about other people’s beliefs.

Honestly, both sides seem to have relatively valid points. However, I agree with the young adult, Nurzal, that I quoted earlier from MalaysiaNow.

“We know this isn’t about politics. This is about our rights. If you think that we are not ready, then you are the one who should change the system and make us understand why we should vote for our country.”

- Nurzal Rifayah Muhammad Iqbal, 18, MalaysiaNow

Instead of questioning whether teenagers and young adults are educated enough or ready to vote, we should question why they are, according to the beliefs of some, not ready to vote in the first place. Improve the system and increase the accessibility of accurate information.

Regardless of our ages, we would all benefit from becoming better-informed voters, so I implore everyone to get out there and learn more about our country and its politics. Happy voting!

Written by Ruby Seet. Edited by Miza Alisya.