Eliminating Learning Poverty in Malaysia: A Conversation with Ms Hema from Projek BacaBaca

The aims and successes of the volunteer-led initiative on a journey to help our children of Malaysia through reading.

According to an article by the Rakyat Post, as of 2020, there were around 1 million children in Malaysia who were not in school. The issue of illiteracy among the children of our nation has always existed, but the COVID-19 pandemic has certainly exacerbated this matter to great lengths. Against the backdrop of the lockdown last year, a group of volunteers came together on a mission to eliminate learning poverty by helping children, one book at a time: Projek BacaBaca.

As the project passes its one-year anniversary since its establishment, I had the opportunity to engage in an inspirational interview with Ms Hema, the founder of Projek BacaBaca, on the project itself, the education system in Malaysia, and what we all can do to help.

Could you introduce yourself and your career to our readers?

My name is Hema Letchamanan, and I’m a senior lecturer at the School of Education, Taylor’s University. I’m also the Program Director for Postgraduate Taught Programmes.

Projek BacaBaca, an initiative under Taylor’s University, was launched amidst the MCO period in 2021. What was the inspiration behind the establishment of this project?

As we know, when the pandemic hit, schools were forced to close. There were many discussions on how this situation would affect children, especially underprivileged ones. Of course, there were some quick fixes, such as donating electronic gadgets and Internet access, but the crux of the problem was not addressed — learning poverty.

Learning poverty wasn’t caused by lockdowns, for the issue of illiteracy had already existed before then; it was simply exacerbated by the pandemic. Thus, students who were poor readers before the pandemic were now even further behind. At the School of Education, we thought we should do something about it. With this in mind, Projek BacaBaca came about to offer an avenue for as many children as possible to be able to learn to read at grade level.

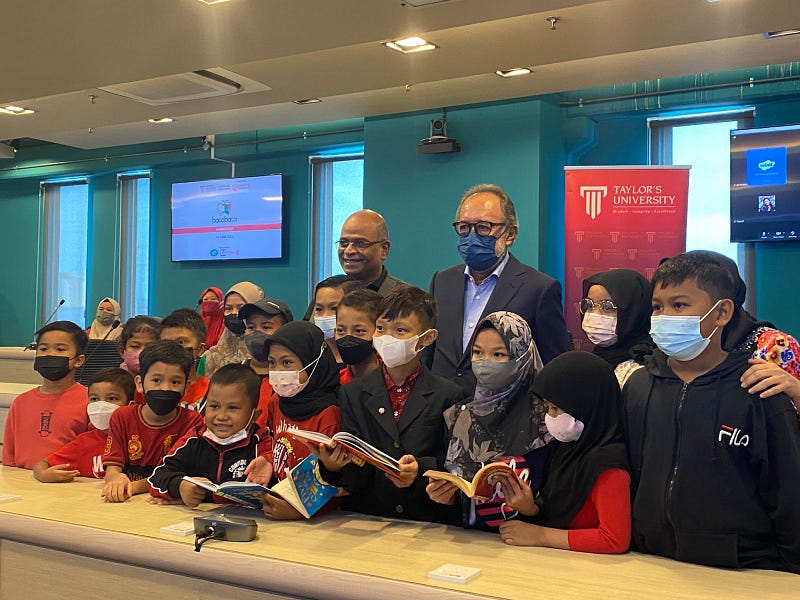

We started last year with a group of 30 children from PPR Seri Alam as a pilot study for six months, where we assigned one volunteer to one child to teach them to read texts in Bahasa Melayu and English. We saw tremendous success with this first phase. There was a jump of about 64% in BM and 86% in English reading improvement. Of course, some of these children were not able to read grade level at the end of the phase, but they had shown clear progress over the course of the project.

That’s where we started last year. We continue this year with a hundred children from six beneficiaries, comprising groups of students residing in Cheras, Banting, Klang, PJ, Sungai Way New Village, as well as Kota Belud in Sabah.

What exactly are the major consequences of learning poverty?

Learning poverty is defined by the World Bank as children who are unable to read and comprehend simple text by the time they are 10 years old. Research in the US shows that if children are not reading proficiently by the time they are 9 years old, they are more likely to drop out of school.

Whilst we may not have such statistics regarding the situation here in Malaysia, it’s safe to say that, if a child is not reading at grade level, they’re more likely to drop out because the child is most likely unable to cope with other school subjects as well, be it maths, science, or geography. I’ve seen this first-hand with the children that I work with in various projects, including children from the B40 households or Orang Asli children, where students in Year 5 or Year 6 are struggling to read even a Year 1 text.

Additionally, these children are not able to experience the joy of reading. When they’re unable to read, most of them would not be interested in reading. Through the help of our volunteers, we hope that children will fall in love with reading because reading truly opens up a world for them, as well as their imagination. Reading allows you to interact with so many different characters across different eras — you can go to the future or the past, right through these stories. Reading shows children what possibilities there are out there for them.

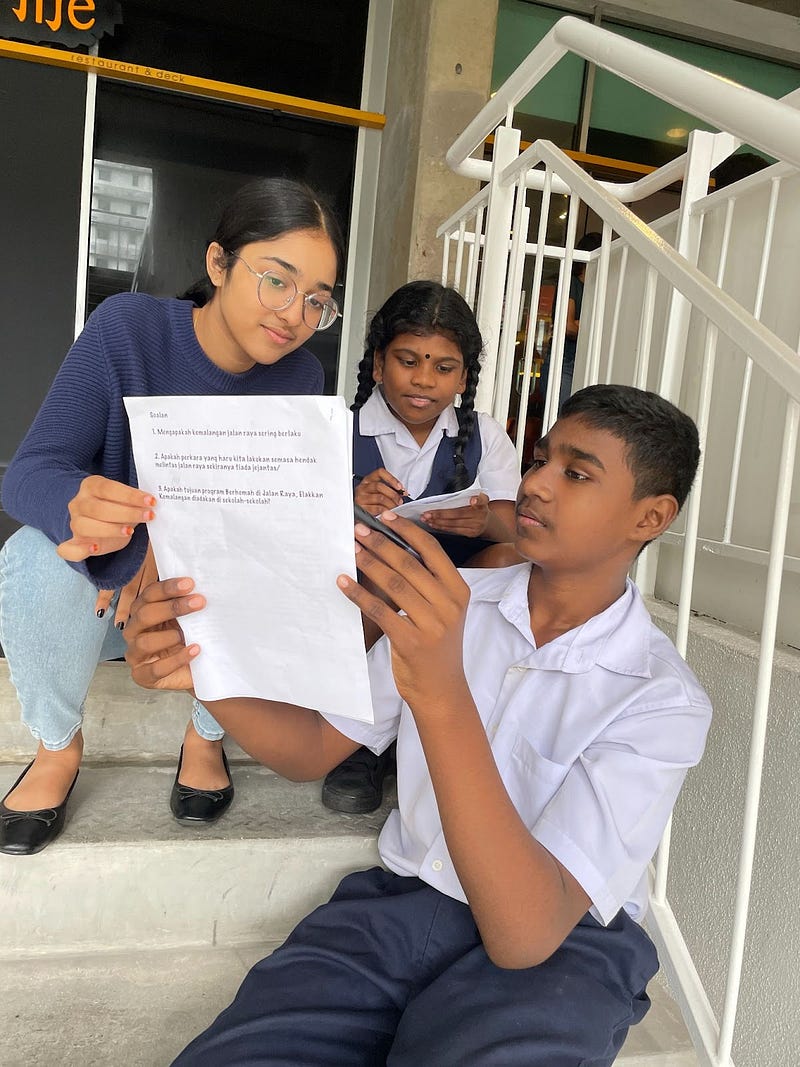

Projek BacaBaca+, which is a kind of spinoff of the original project, was started up recently to aid the learning needs of 11 and 12-year-olds. Could you tell us more about this initiative and the drive behind its launch? What makes this different from the original project?

We started Projek BacaBaca+ to help students in Chinese and Tamil schools to cope with reading in Bahasa Melayu. The Ministry of Education has recently enacted this policy whereby if children from these national type schools do not achieve a minimum of Band 4, or Tahap Penguasaan 4 (TP4) by the end of Year 6, they cannot progress onto Form One directly — they will have to go to ‘remove’ classes, or ‘kelas peralihan’. Little is known about these Kelas Peralihan and their effectiveness in helping students to read at grade level. Besides this, students may lose interest when they have to do an additional year. That could possibly lead them to drop out earlier from school. So we want to try to prevent that from happening by establishing this specific target — to help children from national type schools to cross over directly to Form 1.

The children involved are upper primary students in Year 5 and Year 6 who have yet to meet the band 4 reading level. We had a diagnostic test a few weeks ago, and we have a few students in the programme who are in Year 5, but are struggling to read a Year 1 text. That is the sad reality of some students, especially those who are experiencing poverty, stemming from how our education system is age-based progression. You go through the whole schooling year, and regardless of whether you’ve mastered the foundational skills, you move up one level.

With Project BacaBaca+, we will work with the students for 6 months to hopefully help them reach this reading band (or even higher) during their final school-based assessment by the end of December this year.

Were there any challenges in carrying our Projek BacaBaca? If so, what were they, and how did the team overcome them?

Initially, when we were in talks about setting up Projek BacaBaca, we were thinking of the best platform for this. If we did it physically, we would have limitations with our pool of volunteers in regards to who lives where and whether they can go to the students’ residence areas. If we went online, this would pose an issue for some students who are already struggling with online learning. Still, we ultimately thought we would give the online method a try.

We split our pool of students into two groups: one group, where the students had decent Internet access to have a 30-minute session with our volunteers via Google Meet or other online platforms; and another group of students who would engage in classes via phone calls. We send them printed materials ahead of the class, and during the lesson, the volunteers phone in, and both the child and volunteer will read together. In fact, these are some of the unique features of Projek BacaBaca — we use a broad selection of reading materials to meet the diverse needs of children. The complexity of the materials is aligned to the student’s reading proficiency irrespective of age or year group, and the materials will increase in difficulty as students’ progress. We also use one-to-one pedagogy to ensure a high degree of engagement and use a broad spectrum of technology based on students’ affordance

Aside from that, another challenge was gathering volunteers for the project. Getting 30 volunteers last year was doable, but this year, having to gather 100 volunteers posed quite a bit of a challenge since we had 100 children and needed to match 1 child to a volunteer. Getting them to stay on for a period of 8 months was also an issue since we had some who had to drop out due to personal or commitment issues.

Nevertheless, I’m very much in awe of our volunteers for the dedication they show, because without them, this project could not be a success. We have volunteers from all across Malaysia and beyond: just to give you an example, there’s a volunteer in Brunei teaching a child in Banting; one in KL teaching a child living in Sabah, and one from Sarawak teaching a student in KL.

One beauty of this project is how it brings Malaysians together, hailing from East and West Malaysia. This is the Malaysia I have always believed in: when we see a problem, we come together to try and solve it, irrespective of colour, race, religion, or political affiliations.

We have volunteers from different backgrounds — ranging from students in secondary school, in college or university, professionals, teachers, doctors, lawyers, engineers, and homemakers all banding together with a common knowledge: they all understand the importance of reading. Despite the hiccups we’ve had, the pool of volunteers that we have are of very high quality, and that’s something I’m very happy about.

Projek BacaBaca has been ongoing for a little more than a year now. What would you regard as the project’s greatest achievement thus far?

Simply put, children being able to read. We hear stories from parents about the success of the project for their children. For example, we have this one student who started last year. He was very shy and wouldn’t interact with the volunteer. Fast forward one year: during the launch event we had recently, he read in front of everyone, and was even chosen by his teacher to enter a public speaking competition in his school! We also have the numbers to show the progression of the child’s reading abilities, from diagnostic tests to their end-term tests, but when we hear these kinds of stories, I think that just really shows how much this project has impacted the child’s life.

We also hear stories from our volunteers, who will phone us and tell us how, when they started, they would want to give up since their student was not progressing. What I would tell them is “Be patient — the results will come!”. Sure enough, after two to three months, they’ll come back and tell me, “My child can read!”. One volunteer was even in tears when they told me that their student had asked “How are you?” in an unprompted interaction with them. These are some of the real success stories that we have here at Projek BacaBaca.

This project has helped many young children with their learning and reading skills in the past year since its launch. What are the team’s aims for the coming years?

For one, we hope to scale out this project in terms of getting this idea across to different parts of Malaysia. We may not have the resources to expand to the extent of 500 children and 500 volunteers, of course, but what I hope is that local communities can start their own Projek BacaBaca in their cities, towns, and even in schools where older children can read to younger students.

Another idea is perhaps to see if we can reduce the human element and welcome technology into the project. We’re also thinking of developing an app to support children’s reading in a more personalised manner. Still, at the end of the day, the ultimate goal is to eradicate learning poverty in Malaysia.

This project is most certainly a volunteer-based initiative comprised mainly of student volunteers and professionals, but surely people of all sectors can play a part in eliminating learning poverty in Malaysia. What are some ways in which different parties can contribute in aiding the learning needs of underprivileged children?

Everyone can become a volunteer for Projek BacaBaca! We’re always looking for more volunteers. But even if they don’t want to teach, there are other roles that they can get involved in, such as social media engagement and raising awareness on the issue of learning poverty in Malaysia. Getting more people to talk about it would be really beneficial.

As for our education system in Malaysia, there should be early diagnoses for children. Previously we had tests used to screen students with low literacy and numeracy when they come into Year One, and they would be given remedial classes to get them to grade-level proficiency. That has since been removed after the pandemic began.

I do think there should be a diagnostic tool in place every year; for example, if by the end of Year 1 the child is not reading at grade level, then they should be given some form of additional classes before or during the first quarter of Year 2. Having these targeted interventions would ensure that they’re not just pulled up the ladder without mastering the curriculum.

With the issue of obtaining TP4 in Bahasa Melayu for national-type school students, instead of doing the assessment at the end of Year 6, why not do the assessment in Year 4? That way, we can identify the students who have not achieved the minimum requirement and offer them a chance to improve their reading skills throughout their upper primary school years.

Before we end, is there anything you would like to share with our readers?

I would like to see more people coming together to help children in any way they can, be it starting a book club in our community, or reading to a group of children living in low-cost flats, for reading is so crucial for all children.

My hope is for every community to have its own reading clubs or groups where we can all go in and contribute to helping each other, and for people to take learning poverty seriously. I have seen teenagers in secondary school reading at a lower primary school level. These children and teenagers need our help, and thus, we should come together to help them all achieve a better future in life.

[Transcribed and written by: Siow Chien Wen. Edited by: Teoh Jin.]

Special thanks to Ms Hema and Projek BacaBaca. All photos are courtesy of Projek BacaBaca.