In Search of the Malaysian Chinese Identity

Ethnicity, History, and Identity Politics in Malaysia

It was in my early secondary school that I, mindlessly scrolling through the Facebook feed, with the blessing of the algorithm, boom! stepped on the landmine of rage. It was a photo of a newspaper print I didn’t know, filled with people I didn’t recognize, and interpolated with texts that were too small to read — except the big red title that ran “Apa lagi Cina mahu? (What else do the Chinese want?)” which caught my attention. And that, made me consumed into inexplicable anger.

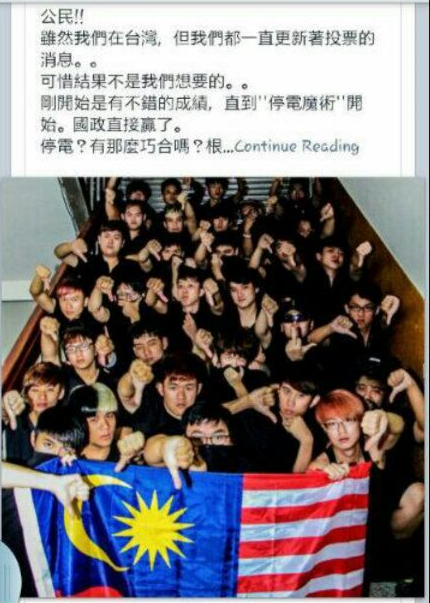

It was the selfsame inexplicability that my anger became weirdly addictive, and almost instinctively, I dived into the fulminating rabbit hole of bigotry and racism. Oh yes, it was an absolute hellfire: comments, with all their overt grammatical errors and raw hatred, are inflicted towards each other to do nothing more than solicit ever-vicious and incendiary retorts. Amidst the limb-strewn altercation, pictures stole most of the attention (of course, in a fit of pique, no one has the patience to peruse assignment-long harangues), and I sure remembered them well. You might have encountered them in banal multitudes, but here are just some that I managed to excavate to induce your retroactive unhingement.

Fortunately, those days of manufactured outrage are gone: at last, I’m wise enough to abstain from social media. Sanity has been restored, and my emotions sufficiently tamed. But to inquire about the cause of such excruciating madness in the first place, I could only open more questions than I could answer. Why was I, with a superficial conception of politics and racial dynamics in Malaysia, so easily embattled into such juvenile outrage? If you could relate, why were you so furious, and furious still when those obnoxious images are dredged up again? Is it because the picture gravely mischaracterizes the Malaysian Chinese community, especially if it’s the community in which you belong?

Perhaps I won’t go mad if so-called “radicals” or “extremists” didn’t instigate my mysterious outrage in the first place. If that was the case, and if that’s probably the reason for the irredeemable conflict in our quotidian public racial discourse, then the problem is close to a resolution: to the best of my knowledge, newspapers and other media platforms don’t, like few years ago, unabashedly foment racial tensions anymore (in fact, the newspaper which wrote that outrageous title was convicted of incitement). Even if the remaining radicals, extremist, bigots, lurking in social media, still defiantly emulate those sins, most believe that they would instantly invite backlash from the internet mob, and possibly the punitive charges from the behindhand legal system. In other words, if we just have faith in the law and the cancel culture vigilantes — a faith that apparently hasn’t disappointed — ordinary netizens or a public person who crossed the line will be duly castigated. Through those means, only time will tell when those bad apples will be completely exterminated from the public discourse, and naturally, people would not be enraged by crass racist remarks, and the contentious topics of race would thereby return to sober diplomacy and amiable compromise. Simple and easy, so they say.

I don’t think I’ll let that pass easily. This is because, importantly, exorcising the “extremist” doesn’t solve the entire problem (if we could see the Covid mania come to an end, I bet the debate about National-type schools, cultural violence and assimilation would return to the centre stage). Since most of us, busying with our own lives, and not putting much thought on our communal and national identity, are, to a lesser extent, the very uncompromising bigots we accuse others to be. The foregoing questions, and the topics of National-type primary schools, cultural violence and assimilation, are difficult but important debates that cannot be addressed with law or internet lynching — self-introspection, which during the lockdown, shouldn’t be in short supply, is the alternative.

I’ll be dissecting the idea of ethnicity through the one I’m most familiar with — hence the title. Plus that the Malaysian Chinese, among other things, are the most-recognized opposition to the status quo, it would be the best specimen to investigate the nature of the idea of ethnicity, identity and culture from their point of view. And of course, the reader has the liberty to extrapolate this discussion onto other racial groups in interest. A caveat of this lengthy (and prosaic) article is that Malaysian politics is also heavily influenced by economics, class differences, and other factors.

What is the Malaysian Chinese Identity?

What is the Malaysian Chinese Identity exactly? When DongJiaoZong (DJZ,董教总, a powerful political player, and an exponent of Chinese Education in Malaysia) proclaims that they are the defenders of Chinese identity, which group does the word “Chinese” refer to? Is it the same group that politicians accuse of being disloyal to the country? What exactly is the identity of the group we call “Malaysian Chinese”? Is there something that unites all supposed members in this group?

One type of response to the last question is that the Malaysian Chinese people are Chinese because they have the so-called “Chinese blood”: they are born into a Chinese family; their ancestors, due to various reasons, left China, and that makes them Chinese. These ideas reside under the umbrella term “essentialism” — the concept that Malaysian Chinese, for example, possess some sort of innate, immutable, abstract quality, an “essence” that “others” are impossible to obtain. This means that Chinese, stays forever Chinese, and the non-Chinese — let it be Indian or Iban — stays in their own “pure” “roots”, “veins” or “spirit” — however to call it.

This is the most intuitive understanding of racial identity, but it has its own problems. Mixed-raced people would be the first to be confused with themselves. Also, in times of globalization and liberalism (the promotion of individual rights and expression), many would spurn such an idea. And hey, isn’t Nazi’s fixation over the “pure” Aryan race that led it to be most notorious fascist, genocidal, authoritarian political entity in the world? Further, as far as peers and adults I know are concerned, they believe the knowledge of their ancestral origins only provide a tenuous connection to the “motherland” mainland China, let alone motivating them to “return” there. Not to mention this idea would strike as absurd if we look at the descendants of the Chinese diaspora in our neck of the woods. People of Chinese ancestry across neighbouring South East Asian regions don’t speak Chinese, don’t have official Chinese names, don’t celebrate Chinese New Year and some are even Muslim. They don’t even think they are ethnically Chinese, at least not in a meaningful way.

The last criticism of the previous paragraph seems to suggest that being Chinese is not something we are, but something we do. Could it be that to be Malaysian Chinese is to act like one? It seems plausible too. The more things we do that are considered Chinese, the more Chinese you are thought to be by the society — like an audition, where the judges, basing a certain rubric of evaluation, after viewing your “performance”, agrees to deem you as Chinese or the other way about. Some common criteria of success such as habitually speaking Chinese, being a Buddhist or some approved synthetic religion, and regularly celebrating Chinese New Year would easily win you a Chinese identity. To put all so far into colloquial terms, the distinction between “essential” and “performative” method of racial identity designation shares the same boundary with the contemporary idea of “race” and “ethnicity”.

Similarly, this definition of racial identity cannot neatly encapsulate all the supposedly Malaysian Chinese demographic. If a Chinese friend of yours is a banana (doesn’t speak Chinese), converts to Christianity, and has an obviously un-Chinese name, would you think your friend is not Chinese anymore? If a black person fulfils every criteria of the “audition”, would we call him a Chinese? The Malaysian constitution believes so when it comes to assigning the Malay racial identity: Article 160 proclaims that anyone who (1) professes the religion of Islam, (2) habitually speaks the Malay language, and (3) conforms to the Malay custom are indubitably Malay. In other words, anyone can be a Malay. If you are a Malaysian Chinese, would you open the door that wide?

Another problem is, who has the authority to establish the points of criteria for being a particular race? Whose standard of “ideal Chinese-ness” is better? How can we know? Should we listen to the government, that people are Chinese because that is what is written in their IC? Should we listen to foreign Chinese scholars and elites from China and Taiwan and Singapore, who preach on pan-Chinese nationalism (中华胶, I made the English translation up), and urge us to assert “our” Chinese cultural confidence? Should we, as the loudest Chinese political representative bodies believe, that the Chinese Guild and Associations (CGA), the Chinese language education, and the Chinese newspaper, are the pillars of Malaysian Chinese identity? Or instead, should you evaluate your own and everyone else’s identity using your personal concoction? If the rule you set by yourself is still provisional, how can we know when it’s perfect?

Does the Malaysian Chinese Identity even exist? Why do we want it so badly?

My peers would, acknowledging the failure of defining racial identity, surrender to the corollary that race, ethnicity, and communal boundaries don’t exist at all. To put it mildly, it has been all along, a pure fabrication. White, black, brown; Malay, Chinese, Indian — those categories are a distinction without a difference, if there is something extant to differentiate in the first place.

I have other ideas. The frustration of finding the correct definition doesn’t indicate that we are looking for a thing that doesn’t exist; rather, it intimates us the intrinsic limitations of language. Language can only get us so far into simplifying and generalizing things according to our experience because our experience is too complex. Language — compared to academic standards — is a crude way for us to communicate feelings of belonging and alienation, giving other people a general reason for the patterns of camaraderie and conflict we feel when we constantly participate in certain groups and interact with particular individuals. When those words are put under rational scrutiny — as done in the previous section — things will become inconsistent, contradictory, lacking clarity that scholars yearn for.

But amid our fundamental incapability of grouping people in precise languages, why do most of us still want to believe the impossible? Why are we so obsessed talking about race? Why are/were we trying so hard conjuring clean cut “imagined communities” when reality doesn’t fit with our simplistic fantasy?

It is important to note that language is for communication, not scholastic inspection. It is true that texts and terminologies have too low of a resolution to illustrate the overlapping, intricate racial patterns and differences, but it is enough, enough to communicate ideas about personal identity and politics. For the former, racial identity is one of the many identities that reliably helps us to fit into the larger crowd with similar backgrounds, interests, or profession, who could better empathize and understand us. Malaysian Chinese tend to befriend/date Malaysian Chinese because the similar racial identity (mostly) correlates with similar first language, background, favourite songs, and political views.

What is more pertinent for Malaysia is the latter reason — politics. For the Malaysian Chinese youth, we have always perceived ourselves as cultural and economic second class citizens, smarting under the status quo. We have been told that the government has wielded assimilationist policies to marginalize the Chinese community in public education, public service, cultural rights, religious and historically symbolic expressions especially since the 1970s. We have been told that the previous generation of Malaysian Chinese activists and politicians tried, among other things, advancing that lion dance should be included into the national culture during the 1980s, Kapitan Yap Ah Loy to be the founder of Kuala Lumpur, and opposing government’s decision to teach primary and secondary school Science and Mathematics in English in 2009 — for the sake of our interest. Even though globalisation has caused the identity of the Malaysian Chinese to gradually fragment and dilute, we have been told that we should continue the enterprise in protecting our communal group, paradoxically with the wider vision of building an inclusive and equitable Malaysian society.

Let’s take a step back and critique this communal narrative for a moment. Historically, people in the geographic region we now call Malaysia didn’t have a clear concept of race. Those sets of vague words — creation of the British colonialists for Malaysia in the late 19th century — are the precedents that, through official documents, media propaganda and economic segregation, gradually shaped the ethnic consciousness in the form of simple filters and labels that most of us unconsciously see through today. It was so powerful and entrenched that the simplistic and distorted propaganda of “Malays, Chinese and Indians” are pervasive from the speech during the day of Independence to the colouring pages in kindergarten schools, as if not mentioning those magical words in appropriate occasions would be called out as unpatriotic.

We have established that Malaysia’s racial profile is more diverse than we can imagine. Not only that there are various subgroups in each of these major ethnicities, they entangle with ethnicities and tribes in Eastern Malaysia and in the deep forest of Peninsula Malaysia. The chaotic diversity was too complicated for colonists to classify. But for the colonists, it was just enough to invent a small set of vague words, each with its extricable political, economic and cultural associations, to pre-empt trans-ethnic anti-colonial alliance in order to stay in power. Post-independent status quo parodied this very set of vague words so that the Malaysian elites could do the same. Those sets of vague words are the treasure of red-herrings, inventory for false antagonisms and imagined scapegoats obfuscating most of the critical issues in Malaysia. It is the constant bombardment of ethno-populist rhetoric that made the “Malays” paranoid, the “Chinese” insecure, and 14-year-old me go nuts when I see “Apa lagi Cina mahu?” — not the extremists. In fact, they only allow an outburst that had been silently brewing in the indoctrinated rakyat.

Of course those propaganda don’t just stir vicious emotions; they also inform policies that impact real people. Those vague words, skilfully drilled into the vox populi, must be accompanied with deeds to reinforce its appeal. Groups who suffer from those policies — Malaysian Chinese, certainly not the worst hit among the many — bear resentment against the tormentors, and have used those very set of vague words to demand recognition and fairness. Time marches to the 21st century, and we are told to mimic their struggle.

But should we? Skeptics believe that using race to destroy racial discrimination doesn’t hasten its demise, but instead perpetuates its longevity. To weaponize those sets of vague words against itself is to bolster the fetishization of race in public discourse, to tacitly believe that those vague words dictate reality when things are not monochromatic as one might think. Another drawback of this narrative is that it stoops us into the language game at which the status quo is adroit. Playing the language game of the opponent is predestined to set us up to failure; the tried-and-true vocabulary like “Chinese chauvinist”, “immigrants”, and “communist” could be employed at all times if we dare to encourage them, which if done, would only cause more heat than light.

It seems that the skeptics believe that those who are upset of the current situation would need to escape from the language game — not to deracialize politics so to say, but to pretend race is not important in Malaysian politics . For the 14th General Election, Pakatan Harapan (PH) chose to attack corruption, cronyism and the 1MBD scandal of the BN government. Those who are English-educated lean on liberal, “Western” ideas of secularism and constitutionalism (weaker central government which is not above the law and equal endowment of basic human rights). For the reasonably desperate activists of today, it seems that the Covid disaster and the slapstick parliamentary circus would be the low hanging fruit. Pragmatists who see wisdom in Lee Kuan Yew on the other hand would believe stable food prices, decent public transportation, and other factors to generally improve standard of living and economic mobility as the flagship manifesto. In short, as long as we don’t touch racial topics, everything will swimmingly move in favour of our reformation.

But that is plain naive idealism! If Mahathir — known for hispro-Malay policies — wasn’t the leader of the PH coalition, I doubt history would end up the one we experienced. The second one is just the fantasy of the urban class. On the third, I might be ignorant, but signing petitions and concerting protests brilliant for casual media consumption seem to be the best thing people can fathom. All in all, It is too preposterous to believe that we could divine some sort of rhetorical acrobatics, an overarching vision that parrys anything that even barely relates to race in Malaysian politics. Race/ethnicity — even if it doesn’t fit with the ontology of Malaysia’s diverse society — pervades every important issue in Malaysia from education to culture, from the public service to the financial sector, from religion to history. There is no escape.

To cull the living flower: the emancipation of the Malaysian psyche

If you are fascinated by quotes and aphorisms, I believe you have encountered Marx’s quote on religion at some point in time — “religion is the opium of the masses,” he wrote. Many passionate atheists have borrowed this quote to suggest that religion is a cheap therapy created by the oppressors to console the oppressed, to provide stability despite its inequity. When the populous feels exploited, dehumanized, religion is thought to be an instant painkiller to your anxieties and gaslighting agony.

But Christopher Hitchens, one of the most prolific English writers in the contemporary world, believed that they have misrepresented Marx’s true thoughts. In his polemic God is Not Great, which he quoted Marx’s Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right:

Religious distress is at the same time the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of the heartless world, just as it is the spirit of the spiritless solution. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is required for their real happiness. The demand to give up the illusions about its condition is the demand to give up a condition that needs illusions. The criticism of religion is therefore in embryo the criticism of the vale of woe, the halo of which is religion. Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers from the chain, not so that man will wear the chain without any fantasy or consolation but that he will shake off the chain and cull the living flower.

To those who still insist on racialized politics, don’t you think it is the opium for you? Isn’t racialized politics an expression of the desire for national harmony and the protest against real national harmony?

To those who want to protect “our communal interest”, don’t you think the worshiping of everything-race is some sort of a nostrum that vouchsafes gratification, but never grace true happiness? Don’t you think this drug — routinely administered by status-hungry politicians who practitioned under colonial overlords — drags us to the desert to pluck an imaginary flower?

I’m not smart or sanguine enough to provide a doable and effective political solution, but my elementary understanding of psychology would serve as a good political self-help. Remember: the way the electorates think determines who is in office; if the minds of the electorates change, people on the top change too. My core advice to the readers is to wean off from racialized politics, by first to remove the source that feeds its metastasis, and later dislodge the tumour which has been fed by the former. In other words, we first recognize and vaccinate ourselves from the absurdity and toxicity of political “leader’s” jarring rants and naive mudslinging, and after that, immerse ourselves in local movies, academic books, online conferences and meetups, documentaries and surprisingly, Wikipedia, to cure our subconscious dogma. It is only that we overcome both the people who write “Apa lagi Cina mahu?” and the impulsive ire when we see those words that Malaysia can recuperate.

It’s all simple to write. I know a silent revolution of the Malaysian mind is not easy. But at least for me, this is the best idea I can think of. After curing ourselves, we could spread the pill to the ill. Write blogs, books, poems, comics, comedic skits, polemics in strategic language choices; share home-made documentaries or novels that show the humanity and diversity of Malaysia, especially during this propitious time we live in now. By uncovering the buried histories and failed movements of Gerakan Sosialis, PUTERA-AMCJA, getting to know visionaries like Abdullah C.D. and artists like Wong Hoy Cheong and writers like Tash Aw and Usman Awang that we can impel ourselves to do better into educating ourselves and others about the ugly truth of racial identity politics, unravel the ineffable beauty of Malaysia’s cultural tapestry, and ultimately inculcate political maturity in Malaysia for the first time in history.

Just like any addictive drug, abstaining from the race mentality will cause withdrawal pains: social costs that would upset the rowdy conservatives and obstinate reactionaries. Even if we are not like them, throwing away artefacts that we have been taught to cherish would make the transition painful for the enlightened too. But if the plan is well-thought, we can make sure the pain is worth enduring.

Thinking is preliminary. It’s time to cull the living flower.

[Written by: Yew Jun Hao]

References:

Revisiting Malaya: Uncovering Historical and Political Thoughts in Nusantara

David Hume, Treatise of Human Nature (Book 1)

Lim Teck Ghee, Challenging Malaysia’s Status Quo

Sharon A. Cartens, Studies in Malaysian Chinese Worlds

Lee Yok Fee, Everyday Identities in Malaysian Chinese’s Subjectivities

Stuart Hall, Cultural Identity and Diaspora

Yao Souchou, Being Essentially Chinese

I would also like to thank 6 wonderful people for agreeing to an interview on this subject.