Plugging the Leaks: A Look at Britain’s Energy Woes

In September, citizens all over Britain had high hopes for the newly appointed Prime Minister, Liz Truss. Liz Truss presented herself as a…

In September, citizens all over Britain had high hopes for the newly appointed Prime Minister, Liz Truss. Liz Truss presented herself as a straight talker; a leader brave enough to assemble bold agendas and adhere to them for the development of Britain’s economy. However, the heroic dream to save Britain’s catastrophic condition quickly collapsed when Liz Truss announced the undertaking of a courageous tax package that soon turned public opinion on her, perhaps leaving lasting electoral damage. A month into her premiership, Truss poorly exemplified the selling points that took her into Downing Street in the first place. The disfavoured action of tax cuts for those high earners has forced a u-turn in her economic agenda. The tragedy began when the Truss administration proclaimed a £45 billion package of tax cuts that would be funded through borrowing.

“I will deliver a bold plan to cut taxes and grow our economy. I will deliver on the energy crisis, dealing with people’s energy bills and the long-term issues we have on energy supply.”

The tax cut was the most significant tax giveaway since 1972; the scheme was not analysed and examined enough by the Office, which led to a bruising and swift response. The pound sank; interest rates ascended; the mortgage market plunged into disarray; The Bank of England was forced to a £65 billion intervention to stabilise wobbling pensions. History books will not articulate kindly on Liz Truss. On her 45th day in Office, Britain’s prime minister flung in the towel amid a series of blows to her leadership. Ms. Truss then thanked her supporters by mistakenly tweeting that she was “ready to hit the ground from day one.” On that, at least, she kept her promise. She had sworn a rebellious new era of economic growth. Instead, she will be remembered for her many U-turns, un-coerced political and financial missteps, and having the shortest tenure of any British prime minister on record.

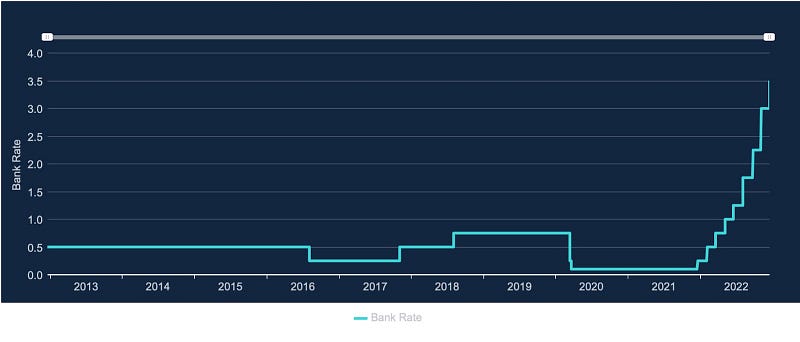

For the time being, Britain’s economy is drubbing. The obnoxious ascent of energy bills throughout Britain and sweeping across Europe has influenced the economy’s productivity and yielded multiple difficulties concerning the spiralling cost of living. Last week, The Bank of England raised the Bank Rate by 0.5% to 3.5%. The monetary policy committee seeks to fulfil the 2% inflation mark while cultivating a way to maintain growth and employment in the nation. This rate rise denotes that the Bank of England has presented borrowing costs at nine sessions in a row, dating back to December 2021.

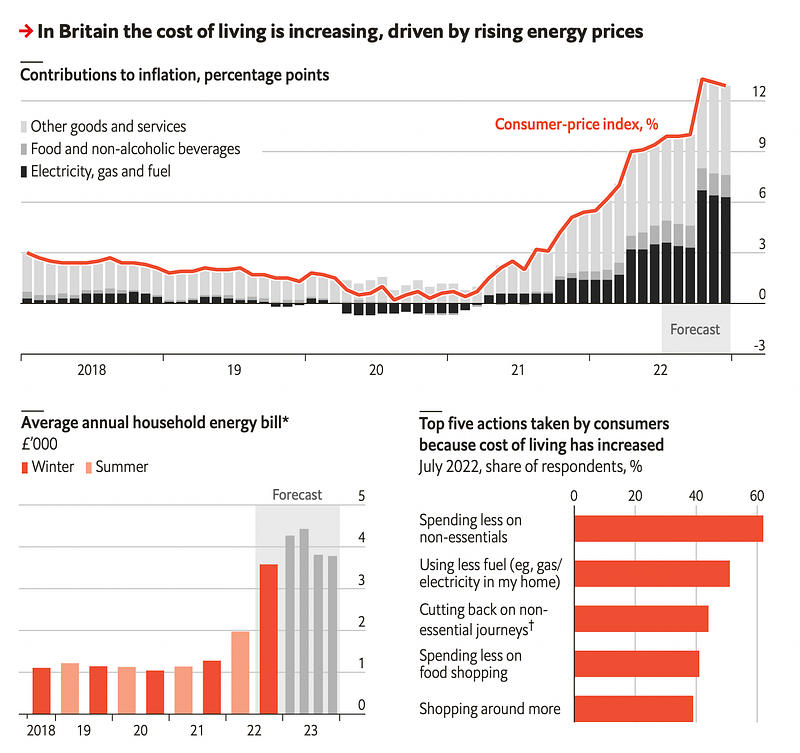

On top of that, news announced Britain’s inflation rate eased slightly from a 41-year high of 11.1% to 10.7% in November. Yet, the whole story that articulates behind this is not always bursts of sunshine and rainbows. Britain, as we know, is currently amid an energy crisis, which is a primary driving factor of the cost of living situation hitting households. An analysis by a consultancy — Cornwall Insight — predicts that families’ average annual energy bills could grow from £1,971 now, already a hefty boost on the prior year, to an eye-watering £4,427 in April.

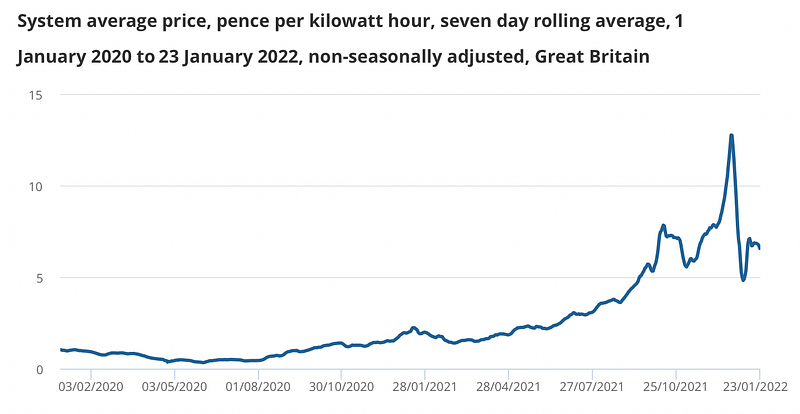

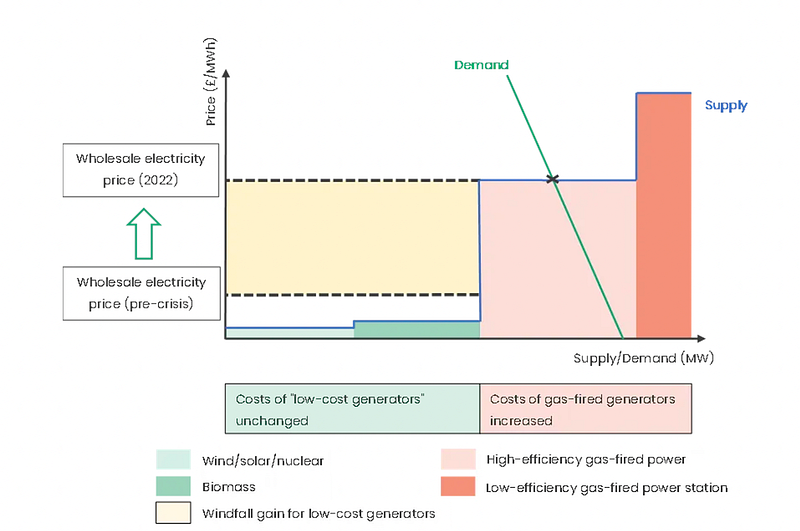

The energy crisis that hit Britain by storm has been piling up over the past year, as demand rose rapidly post-Covid reopening of economies overlapped with Russia’s attack on Ukraine and a subsequent squeeze on gas supplies directly into Europe. Moreover, a steep rise in the wholesale price of gas has eventually driven up the quantity energy providers pay for gas and electricity, and most of the burden is passed to consumers. And as winter approaches, people worry they’ll freeze or have to settle between keeping their families warm and fed. Though current policy interventions have been introduced to facilitate the extent borne by consumers, the consequences are still severe. At present, figures reveal that most of Britain’s gas is imported from Norway, which has now been a primary source for them at around 1,440,000 metric tons, making it accountable for one-third of all substances. Cutting off the gas supply from Russia has not severely impacted Britain with the war persisting in Ukraine, as they rely on less than 4% of their gas from Russia. Countries like Germany will have a significant blockchain effect as they are highly dependent on gas supply from Russia, which will be most affected, with around 55% of its collection.

Generally, Britain depends more on gas as the country has fewer coal plants and nuclear plants. 85% of Britain households rely upon gas for heating more than any nation in Europe, excluding Italy; this is why tension on gas expenses skyrocketed. The emergency leads to a significant share of the population suffering from fuel poverty, where households sink below the poverty bar after abiding all energy bills expenses. The average number of fuel-poor families is currently 6.7 million, up from 3.2 million in 2020. The situation is striking the most impoverished and elder hardest, spending anywhere from 2,100 pounds to 2,800 pounds (roughly $2,400 to $3,200) extra per year on energy. Based on numbers from the International Monetary Fund, the poorest 10% of households will disburse 17.8% of their funding on energy in 2022, corresponding to 6.1% for the wealthiest 10%, representing the most substantial disparity in Western Europe. The U.K.’s National Health Service has also warned of a “humanitarian crisis” for the poor and the elderly, foreseeing a winter of excess illnesses and casualties from freezing.

In addition to the already horrendous conditions of the country, food shortages have become an enormous issue surrounding the energy crisis. Food banks’ usage steadily increases as people cannot afford to pay for food and energy. To give a clear example of the condition that the Brits have to face every day during The Guardian’s Today in Focus podcast, a guest described a story of a resident having to request a neighbour to dangle a single electrical socket into their apartment so they could use electricity (until the neighbour couldn’t afford it, either). Britain, indeed, is plunging deeper into crisis by the day.

Under then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s energy system has undergone privatisation since 1990. Due to the crisis, many small companies went busted at the start of 2021. Those still standing set a lofty fee on buyers, covering the loss of them running out of business and extending the hurdle. But, there is a regulator the Government sets called OFGEM (Office of Gas and Electricity Markets). They effectively formed a “price cap” on energy firms to specify how much retailers can levy households based on an average home’s bill. It would solve a hassle, but when you glance in detail, it’s ultimately established on price per unit, not on the entire usage, so if you utilise a lot of energy, your accounts would still be higher than the cap.

Still, it’s a helpful intervention because without it, as gas prices keep shooting up, runaway prices would spiral out of control. As of the announcement made by Liz Truss, the price cap till the next April 2023 will stand at £2500 means that the Government will cover everything above the threshold. Some still consider this a bar too high as there is a demand for stimulus grants to assist tide people over, equivalent to pandemic payments, where the U.K. government financed 80% of furloughed workers’ wages for over a year. Although the energy package envisions commanding the Government more than its coronavirus efforts, with the ever-rising outlay, time will tell whether any auspices will demonstrate sufficiently or whether despairing individuals will have to divert to dystopian T.V. gimmicks to stay afloat.

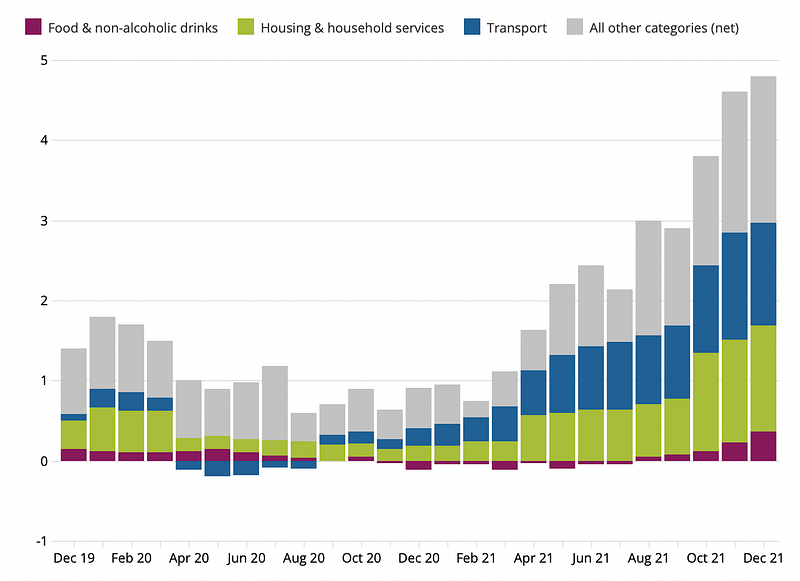

The aftermath can be noticed in elevating electricity, gas, and petrol costs, which hurts households directly and indirectly as these necessary inputs are the backbones in the significant production of all goods and services. Rising food costs have also forced inflation rates to surpass levels not seen in 40 years. The average expenditure allocation of households for domestic energy consumption and fuels utilised for cars concurrently is 6.7%, 3.6% for household energy, and 3.1% for vehicle fuels and lubricants. These ratios are based on 2021 expenses and will likely expand substantially in 2022. It directly has limited on affects consumption due to rising prices and cost shifts. Economists refer to this as highly inelastic demand, where the expenditure allocations for poorer households are immense and, consequently, they partake in a higher inflation rate. The data can be dived deeper in October 2022; the CPI was at 1.16, indicating that the general level of prices was 16% over its value in December 2020. This elevation in price could have been more consistent through numerous energy classes: solid fuels were higher than in December 2020 by 157%, powers, and lubricants by 39%, electricity by 96%, gas by 193%, and liquid fuels by 157%.

European countries, including the U.K., sought to reduce Russian oil and natural gas use rapidly, and the newly completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline was never activated. Indeed, Nord Stream 1 and 2 were sabotaged in a terrorist attack in September, so there is now no direct supply of natural gas to Germany (although other pipelines, including the recent Turk Stream, continue to supply Europe on a smaller scale).

While the Russian invasion of Ukraine has had a significant effect, energy prices were already rising before the war. Partly reflects a ‘base effect’ — costs have increased from a deficient level due to the lack of demand during the Covid-19 pandemic. Recovery in 2020 and 2021 meant that energy prices also came back. Supply problems in the energy industry — common across many other post-pandemic sectors — have also contributed. Increasing output after deficient production caused problems of its own. The global supply chain issues lasted much longer than predicted early in 2021 and only eased by the end of that year. In addition to the direct effect of energy on the consumer basket, it is a crucial input in most goods and services. For lorries to distribute most goods, fuel is required, and electricity is essential for all goods and services. In national accounting terms, energy is an intermediate input into all sectors. As a result, this mechanism has an indirect and more gradual effect of energy on inflation, as energy adds costs to each stage in the supply chains of household goods and services. Further inflation is likely to generate in the coming months.

Rising energy costs will lead directly to an increase in imports. Indeed, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported in its balance of payments report for April to June 2022 that:

‘The goods deficit remained at record levels, increasing to £61.1 billion in quarter two of 2022. High fuel prices continue to affect imports as oil and other fuel imports rose to £29.2 billion in quarter two of 2022, an increase of £4.4 billion compared with the previous quarter.’

Energy prices affect the U.K. government’s tax revenues and public spending, having a significant fiscal impact. The costs incurred by the Government to supply education, health, and other services will increase directly due to rises in energy costs. If public sector wages go up in response to rising inflation, this will also affect government spending.

On the optimistic side, the upsurge in fossil fuel costs will rev the growth of alternative energy reserves, mainly renewables and nuclear. While the development of these will abide by time, dwindling fossil fuel usage will be vastly quicker due to events in 2022. Further, the fall in economic growth compelled by the rise in energy prices will also diminish the consumption of fossil fuels in the countries affected, including the U.K. and the E.U. In the face of the looming climate crisis, this is an unintentional but encouraging side effect.

Delivering a fundamental transformation in energy: What will it take to solve the U.K.’s energy crisis?

1. Targeted financial support for households.

The Government should execute a new, expanded support scheme to supersede the actual Cost of Living support scheme. For the first time, this latest scheme should contain extra payments to families with children who face additional energy costs. The 2023 scheme should incorporate the following:

• £1,000 in help for every household, paid as a credit on their energy bills

• Plus £1,000 for those, including pensioners, on means-tested benefits

• Plus £500 per child for those claiming Child Benefit, up to an utmost of two children

• Plus £500 for people with disabilities.

These payments should reach in six monthly installments during the winter months (January, February, March, October, November, and December 2023), reflecting that energy bills are significantly higher during winter. To help those requiring further support, the Government

should add £2 billion to the Local-Authority-led Household Support Fund. The 2023 scheme would cost an estimated £47.3 billion.

2. A serious campaign to cut energy demand

In a short period, the finest way to lower market prices for energy is to cut demand, and the Government must be forthcoming with the public about this. Ministers should:

•Launch an energy-saving movement for households and small businesses.

•Present a new energy-efficiency obligation for landlords and housing establishments.

•Mandate energy-saving measures for companies similar to those executed across Europe.

3. Pressure to see through a radical, green transition

Despite the U.K. getting nearly 30% of its energy from clean sources like wind, solar, and hydropower, the country has withstood climate warnings with as many as 100 new oil and gas licences granted and 900 locations for exploration. There is also an active anti-green lobby taking essence in Government, with ministers expecting to ban solar projects from most English farms.

What should be occurring is a tremendous expansion of wind and solar power. It’s also vital to build integrated systems, where we all have solar panels or windmills in our homes, and you have direct current systems locally, where communities increasingly can make their electricity. Those are the sort of transformations that have to happen long-term. Green energy sources would protect the country from fossil fuels and decrease polluters’ lobbying power. The U.K. not only needs to finance green energy laboriously, but it also needs to adopt a radical policy that would haggle with both class inequality and the climate crisis simultaneously. A Green New Deal would propose this. For Green New Deal Rising, a climate justice campaign group, this looks like building an economy based on 100% clean energy. Creating protected green jobs and guaranteeing a just shift for those currently working in the energy sector, transforming the overall economy, protecting habitats and carbon sinks, and ensuring the provision of clean water, air, and green spaces, as well as promoting international justice to account for the U.K.’s historic and ongoing function in exploiting resources.

The Britain energy crisis has been a significant issue for the past few decades. With the increasing energy demand, the country has been struggling to meet the needs of its citizens. The Government has implemented various measures to reduce energy consumption and increase efficiency, but the results are mixed. The country has also been exploring alternative energy sources, like wind and solar, but these have yet to make a significant impact. Despite the efforts of the Government, the energy crisis in Britain remains a considerable challenge.

In conclusion, the Britain energy crisis is a complex issue that requires a multi-faceted approach. The Government has taken steps to reduce energy consumption and increase efficiency, but more needs to be done. Alternative energy sources, such as wind and solar, should be explored further to reduce the country’s reliance on fossil fuels. Ultimately, the success of the energy crisis in Britain will depend on the collective efforts of the Government, industry, and citizens to reduce energy consumption and increase efficiency. Only then can the country hope to achieve a sustainable energy future.