Why Learning About the History of STEM Matters

In 2018, it was a different November for me. I was in Yanqing, 100km away from the capital city Beijing. As a proud tropical country…

In 2018, it was a different November for me. I was in Yanqing, 100km away from the capital city Beijing. As a proud tropical country citizen, the late autumn temperature of negative 4 degrees tormented me. My fingers stiff, desperately cornered into my pockets by the creeping cold; my lips crinkle, helplessly terrorized by the arid hail; my legs shiver, silently screeching for the Sun’s salvation. In retrospect, suffering from cold without encountering snow was a horrible trade-off.

Yet, at that moment, I was not yearning for snow. Near midnight, stuffed under layers of clothes and jackets, my friends and I, like scattered sticks, were laying on the freezing concrete floor far from our stay. We didn’t play truth or dare, we weren’t trying to hibernate either — the sky had just cleared up.

Just to give you some context, my friends and I were taking part in an astrophysics Olympiad competition. Looking at the night sky each time when we go out is a shared foible among nerds like us. But nerdiness is not the sole reason we love stargazing and astronomy as a whole. We love those because they are beautiful. As clouds started to dissolve away, the pitch black background revealed sprinkled crystals varied in hue and intensity. At the northern direction, Mother Bear, waddling ponderously, was pursuing her little bear, which was playfully gambolling in circles; near the rigid horizon, Orion the hunter had just woke up from his slumber. Around the waist, the tip of his sheathe glows in pink, a vestige of a dying star after an extraordinary explosion; amid the celestial drama, the Milky Way galaxy stretches athwart the firmament, its elegance stealing the centre of the cosmic stage; For those who have good eyesight (for me I’d just use binoculars), you could see a soft blurry oval under Cassiopeia the Queen — that is the Andromeda Galaxy. In 4.5 billion years, it would collide with our Galaxy in a catastrophic spectacle, and when that happens, Earth could be flung by the gravitational dance into the void, or remain with her family, to witness the birth of new stars and the death of old ones around her backyard. Somehow, elegant equations and fined-tuned universal constants craftily finesse these astral arts of majesty.

Of course, beauty is not exclusively privileged by star lovers. Such admiration to nature is the reason why some people “just” like to study animals, solve mathematical problems, or discover new chemicals for their entire lives. I understand that STEM subjects have a treasure trove of practical applications to benefit the society, but many scientists and mathematicians just love their subjects for the sake of its aesthetic inspirations, as Henri Poincaré said:

“The mathematician does not study pure mathematics because it is useful; he studies it because he delights in it and he delights in it because it is beautiful”

— Henri Poincaré, French mathematician

However, aesthetics and practicality are not all. I feel that many people around me understated another major attraction of STEM — the history of it. The history of STEM has been under-served; its richness barely transpired during science lessons, its significance unfairly diminished within the public consciousness. As Covid-19 and the latest Industrial Revolution kicks into gear, science would become more and more intertwined with humans, and whether it’s widespread STEM literacy or an expanding STEM labour pool, more people must be able to develop a healthy relationship with science for a better society. Learning the history of science is a crucial element to propel this virtue.

So what makes the history of science worth learning?

1. It restores the human side of science

The history of STEM confides us the clumsier sides of geniuses in other aspects of life. They are the trailblazers in their field, but they’re normal humans too, like us, prone to volatile feelings and emotions, entangled in the strings of power, pressured by suffocating social expectations. By chance and faith, they open new avenues of possibilities.

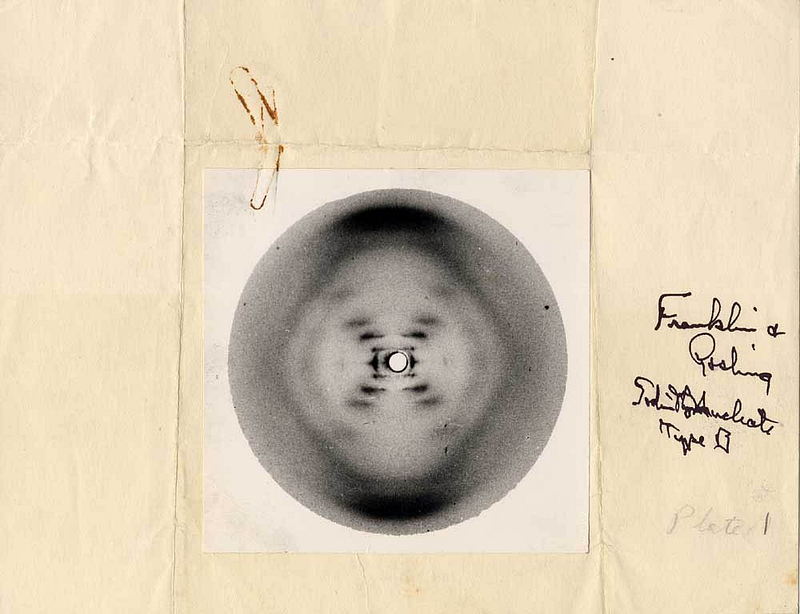

Rosalind Franklin is one of many female scientists who were unappreciated with regards to their contribution due to mere gender. She is the major scientist that led to the discovery of DNA’s structure using X-rays, but her breakthrough insight was secretly shared by her senior staff to two scientists, whom along with the senior staff, earned the Nobel Prize afterwards. She was not credited for her work because Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously — she died of ovarian cancer. Even so, her male colleagues didn’t show gratitude for her effort. The best they could say about her is that she was an “assistant” or that she “didn’t know any organic chemistry”.

The details of the anecdote are still fuzzy, but many women and stigmatized minorities, bewitched by Rosalind and other scientists’ unalloyed passion for knowing and unflagging creative determination, is sufficient to inspire them to beat the odds and engage in STEM.

A slight reflection also imbues a whole new spirit to the each page of a science or maths notebook. Every time you are grinding through textbooks or practise papers, be aware that each scientific knowledge — including the wrong ones swept away from our syllabus — is a diary of one’s “A-ha” moments, a memoir or one’s lifelong conviction, a chronicle of one’s travails. With a slight change of perspective, science becomes much more interesting. It is not only about memorizing facts and equations, but also preserving and recounting the eventful life of passionate intellects, and hopefully authoring of our own.

2. It educates us the science fundamentally influences the world

Big ideas change the world. They invite criticism, they influence new thinking. Some of them, inspired by big ideas, left a mark on our history textbook, while some, left a scar on it. Science is a well-spring of big ideas, and they aren’t alienated from these tendencies.

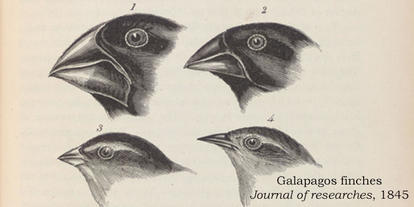

Darwin’s theory of evolution is the exemplar of this. Celebrated as the genesis of modern biology, his theory of natural selection (the survival of the fittest) among tortoises and barnacles, stirred some to see human society in a similar light. In the UK, as colonialism was on its peak, people started to modify Darwin’s ideas to justify racism and imperialism. From traditions to different skull sizes, academics started to find specific human traits to sift people into a hierarchy of superior and inferior “races”, and superior ones should re-engineer foreign societies to accelerate human “progress”. Eugenics, the practice of breeding “superior” beings and precluding blending them with “inferior” groups, was born. In the 20th century , the US government forcibly sterilized prisoners and LGBT groups lest they breed “degenerates” that overpopulate the society. This idea rears its ugly head when the Nazi’s assert themselves as the superior Aryan race, feeling morally obligated for the culling of Jews. The word eugenics might be tainted forever, but it doesn’t stop the idea obstinately seeping into the crevices of modern societies. Be mindful when you encounter IQ fetishism or Thanos-like sentiments; those ideas could be traced back to Darwin’s ideas.

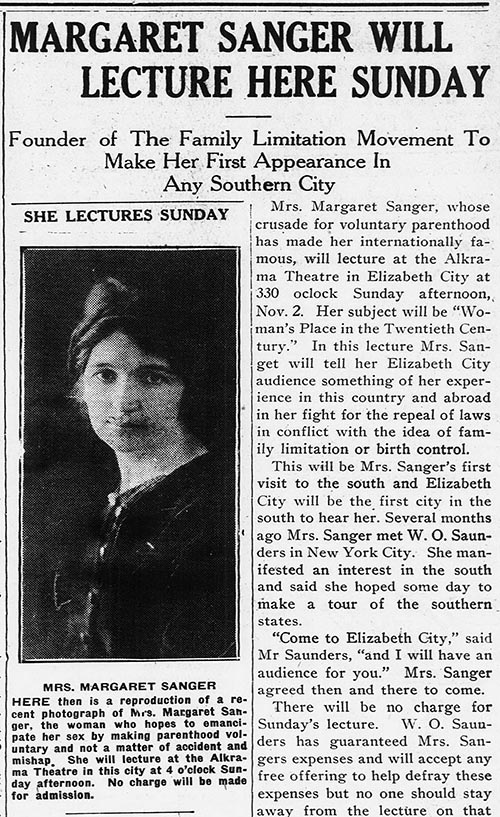

But as history continually reminds, nothing is black and white. There is a silver light under the misuse of Darwin’s theory. Margaret Sanger, a women activist, capitalized this eugenics buzzword (which undoubtedly invited controversies), started to popularize the idea of birth control and contraception. The call for women reproductive self-autonomy and purge from suffering of unintended pregnancy and the following fateful abortion reverberated across the globe, impugning social norms and catalyse progressive movements. In other words, science is a powerful tool to change the world.

3. It forces us to confront timeless ethical dilemmas

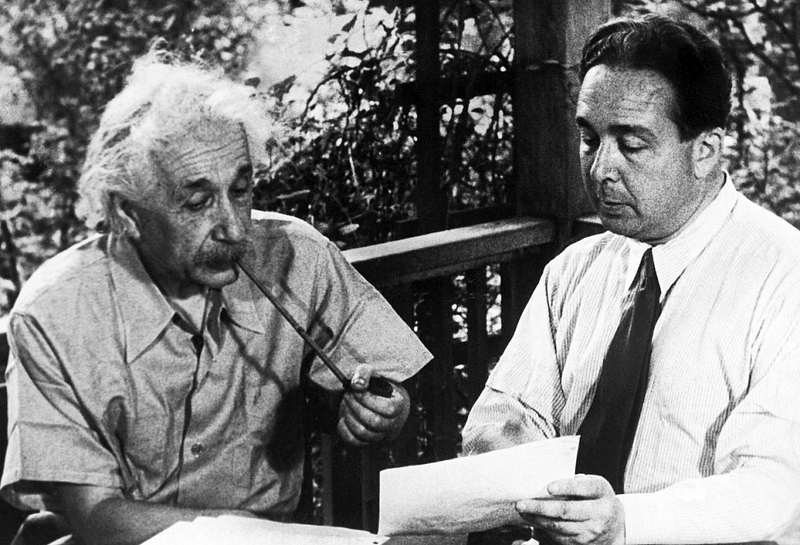

We can change the world, but should we? It is a timeless dilemma that is broached again and again in the history of science, and the consequences of those questions are not trivial. As many might remember in their history lessons, the detonation of atomic bombs in two Japanese cities exposes our power to destroy the world with a press of a button. However, it is neglected that the Manhattan Project, a clandestine state-sponsored nuclear bomb research project, was persuaded by Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard (a physicist) in a letter to the incumbent US president to prevent Nazis from obtaining that superweapon before the United States. The weapon was not put into good use as the Nazis were defeated, and the US made an unnecessary action to detonate two atomic bombs on the emasculated Japanese Empire — a noble cause turned into an unforgivable sin.

Around the 1840s, Henry David Thoreau, an aspiring American writer, shut himself from the bustling, materialistic lifestyle of city dwellers, decided to build a small house near the serene Walden Pond in the woods. During his years of solitude, he recollected his days as a trader of him witnessing the booming technological progress in his city. He hinted that investors seem to carelessly create technology for the sake of technology, often in a ludicrous manner, as he wrote in his seminal essay:

“We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate[…] We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the old world some weeks nearer to the new; but perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad flapping American ear will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough”

— Walden, Henry David Thoreau

His criticism seems frivolous at first sight, yet it uncoincidentally resonates with the current relationship with our gadgets. The fruit of brilliant Silicon Valley genius, who envisioned a world of democratized information, practically ended up as the 21st century unregulated substitute of cigarettes and alcohol. Like the nuclear bomb, its intention is terribly removed from its true use in the present, and hence we became tyrannized by the world we created ourselves. I could stretch this argument, as speaker Sam Harris did, to the construction of AI. Whether by cultural aggrandizement or economic necessity, Artificial Intelligence would continue to be refined and enhanced. As AI inches closer and closer to human intelligent capacities, would autocrats use AI to oppress reactionary voices? Would multi-trillionaires reel over Elysian lives on other planets while the vast poor emaciated on the inhospitable Earth? In other words, are we socially and politically mature to handle a cyber-nuclear bomb? To respond to this, we would need AI engineers that are not only obsessed over coding and algorithms and philosophers that only bother ancient texts.

4. It humbles humanity

A different perspective on the history of science humbles our intellect, and questions our assertion as the paragons of rationality and deliberation. We are naive, yet omnipotent trouble-markers that are still wrestling to grow up and correct our childish, uncalculated errors. Solving one problem opens new unexpected set of issues: we invented CFC, a chemical superpower that exists in air-conditioners, shaving creams, aerosol cans, only to know decades later that it punctures the protective layer of ozone we living things depend for survival; we added Lead to fossil fuels to improve efficient automobiles, only to realize that Lead suspended in the air stunt child growth and kill car engineers; we flood our crops with artificial fertilizer, only to remorse the health adversities and pollution effects to farmers and the environmental (the last one yet to be solved).

Studying history of science also unveils our manifest ignorance about the world. Just take a quick historical tour of exploration of the true nature of matter. Plato imagined all matter to be composed of inseparable perfect geometrical shapes. Much later, alchemists in the Islamic and European sphere believed one can change copper to gold until Dmitri Mendeleev refuted the claim and invented a systematic way to arrange different elements using the periodic table. Marie Curie laid the foundation of radioactivity, shocked scientific with the fact that atoms, previously thought to be indivisible, can be split into smaller atoms. As swift as one can imagine, Albert Einstein overturned the whole scientific establishment again, with its famous E=mc². Later, a horde of quantum physicists caught Einstein in disbelief, postulating the wave-like nature of particles and physical laws that lie beyond our intuitive understanding of things. After a winding journey, scientists are still not confident enough to answer the question “what is stuff?”. More is yet to be known, and scientists are the humble students that are still doing Nature’s homework. Some of us might have to learn one or two of so-called “epistemic humility” surrounded by sententious tirades and chronic echo chambers.

5. It empowers humanity as well

If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.

— Isaac Newton

Consuming any portion of the history of science would tell you that science is accumulative. People build on ideas established by others and thanks to all their work, we, as so called, feast on the labour of centuries. We are standing upon the shoulders of giants. And also remember, those giants are not only the popular individuals of Johann Gutenberg, the Wright Brothers, or Ibn Sina, but also unidentifiable names behind the discovery of gunpowder in China, the invention of algebra in Arabic nations, unrivalled engineering achievements during the Roman empire, and the experimentation of medicine in ancient India. Without the people of yesterday, this particular group of apes wouldn’t become what we are now today.

So, do you want to be the giants of tomorrow?

[Written by: Yew Jun Hao]

Inspirations:

Mastery, Robert Greene

Energy- a Human History, Richard Rhodes

What Makes People Engage in Math, Grant Sanderson (link)

A Mathematician’s Lament, Tibees (link)

Cosmos- A Spacetime Odyssey, a documentary series hosted by Neil deGrasse Tyson

The Theory of Everything, a biographical film of Stephen Hawking

Crash Course History of Science, a YouTube educational series hosted by Hank Greene (link)

The ridiculous way we used to calculate Pi, Veritasium (link)

Walden, Henry David Thoreau