Xinjiang Cotton Controversy and the Widespread Cancel Culture in China

On 26th March, popular foreign fashion brands in China with the likes of Swedish H&M and American Nike found themselves in hostile…

On 26th March, popular foreign fashion brands in China with the likes of Swedish H&M and American Nike found themselves in hostile territory overnight. All of a sudden, their products were shunned by Chinese consumers and their physical stores completely shuttered or avoided. This is one of the many cases where the increasingly sensitive public in China has taken to great lengths to tell foreign critics and sceptics that once a red line has been crossed, consequences will follow. Past examples included the Philippines who found its fruit exports affected by deliberate export restrictions over Scarborough Shoals disputes; South Korea meanwhile found its largest supermarket chain Lotte sanctioned by Chinese authorities over THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense, an American missile defence system) installation disputes. The most recent example would be the trade dispute between China and Australia, which saw its wine and iron ore exports to China, its largest trading partner, plummet. All of these including the Xinjiang controversy, which would be discussed below, show a steep rise in nationalism and increasing tendencies where regular citizens would support or even call for such measures when public opinion of another nation is against China.

What sparked the furore of Chinese consumers?

A year before the unexpected boycotts, H&M posted on social media expressing concern over labour abuses as well as the general human rights landscape in Xinjiang and pledged that they did not use cotton sourced from the region. This did not have any immediate ramifications as emotions in the country remained mostly reserved. One year later when Western governments began to level sanctions on Chinese government officials for their alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang, the general opinion among consumers was skewered against foreign criticism of any form. The main reason for such backlash is largely due to the aforementioned rising patriotism as well as the feeling that these criticisms were uttered with malice in an effort to smear the country’s reputation.

The above social media post is one of many that followed what was believed to be the first that kickstarted the boycott which was published on a state-affiliated account, the Communist Youth League. ‘Xinjiang Mian Hua’ is clearly a play on words found in H&M’s logo and the caption below translates into: ‘ I support Xinjiang cotton’ thus showing the poster’s support for cotton exports from the region. As state-funded news agencies jumped onto the bandwagon shortly after the movement gained momentum, the boycott had begun in earnest. The boycott has since widened to include Burberry, Adidas and Converse, among others. Some companies’ online shops are blocked and their stores have vanished from digital maps. For example, it is no longer possible to hail a taxi to physical shops using Didi (China’s equivalent of Grab and Uber). Consumers are also unable to shop online as popular e-commerce platforms such as Pinduoduo, JD.com and Tmall have removed access to the affected companies’ online stores.

Given that the movement is now far beyond its point of no return, what’s next?

Just as they dealt with foreign competition in the space of browsers and social media platforms by banning Twitter and Google which helped propel the growth of local alternatives such as Weibo and Baidu respectively; the boycott of foreign fashion brands likely will see a huge amount of consumers redirected to local brands like Li-Ning and Anta. The official narrative has supported this as well by increasing the promotion of these brands on all channels of communication. While staff members and employees of the foreign brands affected by the boycott would suffer in the short term, the government and to a certain extent individuals believe that this is ultimately for the greater good. This is due to the massive success that local alternatives were able to make after the foreign competition was forced out of the country in the early-2010s. Even Huawei could thrive with Apple and formerly Samsung fighting for dominance in the Chinese smartphone market. Just as Malaysians would feel proud when our products thrive elsewhere in the world, the Chinese public would have a similar sentiment albeit such growth was only possible in the absence of any competition.

Perhaps, the fact that these sanctions would eventually end would be of some consolation to the companies that had inadvertently become the casualties of this boycott. This is seen in the case of Lotte as mentioned above after the group sold land to the US Military for the purposes of installing THAAD. Two years after the boycotts began, the group was finally relieved of the economic pressure exerted by the government and to a lesser extent the public. However, given the fact that Lotte had in fact sold off most of its holdings and planned to leave the Chinese market when the decision to lift the sanctions were made, this is likely still bad news for the fashion brands affected.

These are the consequences that the retailers have to bear after invoking the anger of the Chinese government and consumers. This was not really unexpected as many thought given that China as a whole had been extremely sensitive surrounding the issue of Xinjiang. The sensitivity in this regard is even more so than other disputes that the international community disagrees with China such as the South China Sea dispute or Taiwan. This is understandable given the gravity of the allegations was on a similar level as Nazi Germany’s concentration camps or the Soviet Union re-education camps and gulags.

Brief Summary on the Xinjiang controversy

In short, devastating attacks and riots that were allegedly organised by separatist forces whose objective was to establish the independent state of East Turkmenistan (historically a state established by Soviet-sponsored warlords) rocked the region in the 2010s. The Chinese government established, in their words, vocational training camps. Meanwhile, from the perspective of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) as well as those who escaped and the international community, de facto re-education camps. The Chinese government vehemently denied these claims as outrageous slanderous statements from Western pundits and governments. The state-sponsored media outlets also did their best in pushing the state’s perspective saying that the camps are either vocational camps or the images simply showed regular schools. A 2019 attempt by VICE News journalists posing as travel bloggers to enter the far-flung and heavily surveilled region which restricted journalistic access showed a completely different picture:

Streets were empty, checkpoints every few kilometres, cameras in every possible location, policemen in riot gear patrolling the streets, need I say more? This is perhaps the closest adaptation of the Orwellian dystopian world in the 21st century. Xinjiang is for all intents and purposes a police state. Then, the issue of forced labour first leaked from the region when the pandemic began in early-2020 with reports indicating that the persecuted Uighur minority were sent busload by busload to factories intended to produce PPEs (Personal Protective Equipment). This would later simmer into the current dispute where Western fashion brands in an attempt to adhere to ethical standards commonplace in the West, denounced such practices, which eventually caused the boycott. Of course, not all nations are against these measures in Xinjiang. According to Global News, a state-affiliated news agency, at least 90 countries supported these moves at the UNHRC’s 47th session. Although, it must be noted that these countries are themselves not democracies. In fact, the representative that led this motion is from Belarus, commonly known as the last dictatorship in Europe.

The situation in Xinjiang would likely remain the same for the foreseeable future, with the Human Rights Watch portraying a sombre future for the population which are to this day still persecuted by the authorities.

Review of Cancel Culture in China and the reparations of this boycott

This boycott can be said to be caused by not only pure nationalism, but the factor of self-censorship is also extremely prevalent considering whenever cancel culture is seen in Chinese media, their reaction time was almost always faster than official media agencies. The reason for this is simply the conditioning of several decades of intense censorship policies from the central government had encouraged the use of self-censorship to appeal to the authorities who can in theory ban any networks on a whim when unapproved content was broadcasted either deliberately or negligently. The image above is a still from a popular Chinese reality show, can you spot the blurred out shoes of the performer? That is self-censorship at its finest, without interrupting regular programming, the network simply had to filter out unapproved content, in this case, the pair of Nike sneakers worn by the performer. In addition to these, various celebrities such as Wang Yibo, Huang Xuan and Victoria Song who have served as brand ambassadors for these brands released statements that they were severing ties with the brands, with one noting that “the country’s interests are above all”. The fact that they had done so even with the potential need to pay compensations as stipulated in their contracts with the company shows that they are either cautious not to offend the authorities or they truly believe the government’s narrative and support it. However, this is also one of the instances that the Chinese public had in fact participated in a grassroots movement albeit not a political one seeing that the boycott took effect in less than 48 hours.

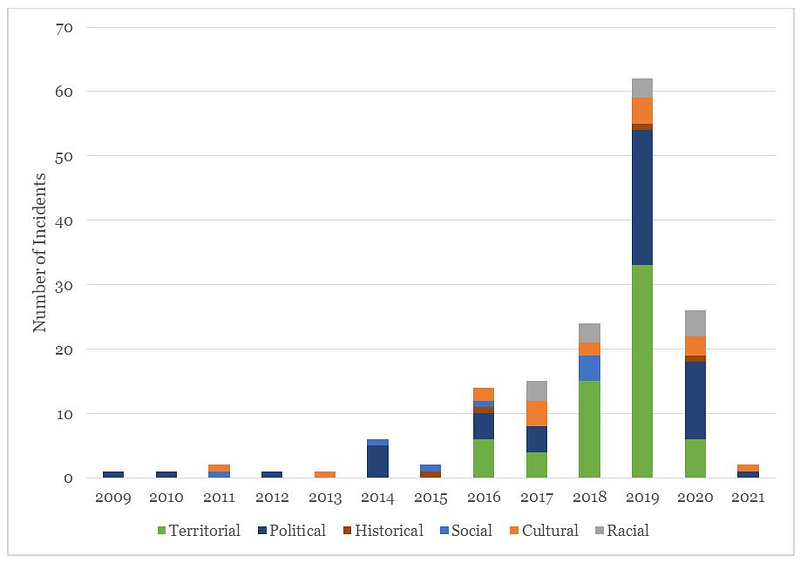

This figure shows the instances when the backlash against an international brand occurred in China. As shown, the year 2019 saw many instances of cancel culture being weaponized to attack foreign firms for mainly racial and political reasons that year. The losses that these companies would sustain is simply immeasurable as in the case of Lotte they lost all market share in the country weeks after stores were ordered to close for excuses made up by the local government. For now, the foreign brands can only hope that the situation in the Chinese market would soon return to a position where they are no longer vilified. In conclusion, the controversy and subsequent boycott would likely not be the last seeing that China and the West are increasingly at odds given their difference in core values, systems of governance as well as trade disputes.

Cancel culture which would be used to enforce or advance certain moral or social values in other countries is sadly only a political tool or weapon in China to attack firms that are not aligned with the government’s viewpoint. The public will also continue to self-censor themselves until the state’s censorship policy or apparatus lets up, however that might not occur in your or my lifetime, given that it would probably require a change of government in China.

[Written by: Christopher Lim Min Jie]